Posted: April 3, 2024

Community scientists work to protect Pennsylvania's wild bees

Photo credit: adobe stock mathisprod

Remember that old commercial for the McDonald's Big Mac? When Susan Janton, a Penn State Extension Master Gardener from Cumberland County, talks to her community about the importance of wild bees, she starts by singing the jingle: "Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions, on a sesame seed bun."

"Without bees, you would not have all the fixings," she said. "There would be considerably less onions, pickles and even sesame seeds. To have a tasty and healthy diet, we must appreciate the pollination efforts of bees."

Bees pollinate a large proportion of the flowering plants on the planet, explained Margarita López-Uribe, associate professor of entomology in the College of Agricultural Sciences.

"Pollinators are crucial for food security and the sustainability of food production," she said. While not all pollinators are bees, López-Uribe pointed out that bees are the most important pollinators for the major groups of plants.

Pennsylvania is home to a wide range of crops, including apples, cherries, blueberries, pumpkins and many others that depend on pollinators such as wild bees for successful production, said Valerie Sesler, Master Gardener area coordinator for 12 counties in southwestern Pennsylvania.

"One-third of the food we eat requires pollination by bees," Sesler said. "That really hits home when people think about what would happen to us if we didn't have bees and other pollinators providing the food we eat every day.

"These pollinators contribute to the yield and quality of crops, supporting the state's agricultural economy," she continued. "They help maintain the genetic diversity of plant populations in natural ecosystems, which is essential for the health and resilience of Pennsylvania's forests, meadows and wetlands."

To better understand Pennsylvania's wild bee population, 20 Penn State Master Gardeners partnered with López-Uribe's lab for long-term bee monitoring research. The lab does not monitor honey bees, but rather wild bees, with Pennsylvania hosting more than 400 species. López-Uribe pointed to the significant gaps in knowledge of bee biodiversity across the state as an inspiration for the project. While ample information about bee diversity existed in counties with research universities, some counties had only two bee species recorded before the beginning of the study.

Penn State Master Gardener Laura Jackson collects samples for a bee monitoring project. Photo: Penn State Master Gardener Program

"Another motivation for this project is our awareness that bees are in trouble," she said. "We're seeing fewer insects than we did a few decades ago."

The researchers aim to inventory bees from across the state to understand the abundance, location and distribution of species.

"The data enables us to see if bee ranges are shifting or if they are disappearing from some areas while appearing in places where they were not previously recorded," López-Uribe said.

Her lab trains Master Gardeners to follow standardized protocols that take into consideration the ethics of collecting insects for natural history preservation. Janton said volunteers learn how to sample bees and record specimen data at a museum-quality level.

Master Gardeners use several methods to collect bees, including traps and nets, in locations determined by each participant. Janton tries to net bees twice a week in different locations.

"There's an art to netting," Janton said. "It's like learning golf. You have to have patience, swing quickly and flick your wrist. It took me a few weeks to learn the netting procedure."

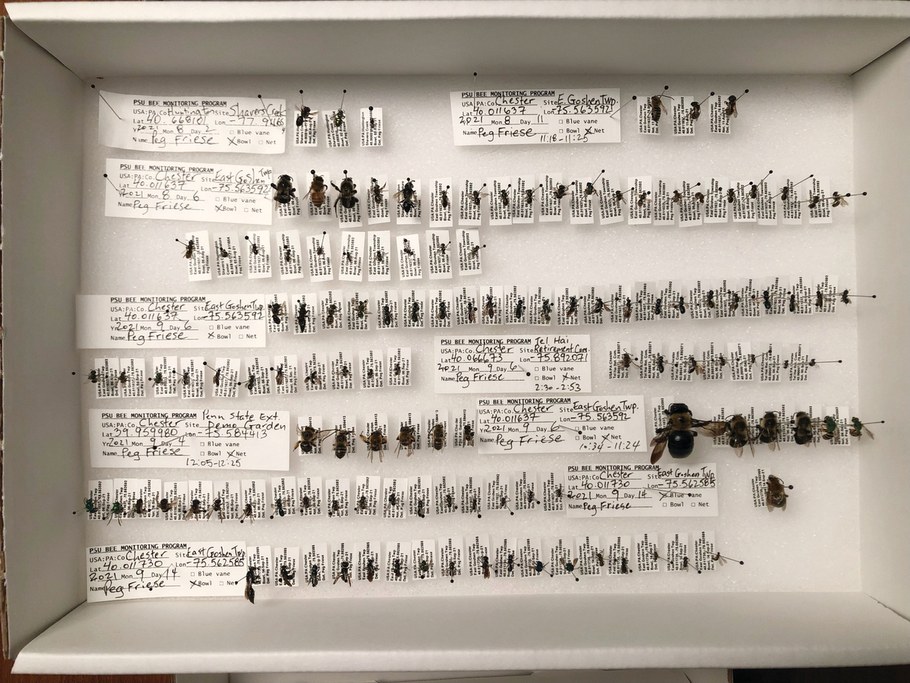

Participants keep detailed records about where they collect the insects, the environmental conditions and the types of plants the bees visit. They wash, dry and pin the collected insects before sending the bees to the López-Uribe lab for final identification.

"Since Master Gardeners already have some training and knowledge of entomology, their participation in this research project provided an advantage in identifying bees from other insects," Sesler said.

So far, Master Gardeners have collected about 9,000 bee specimens and more than 240 species — including data on bee species previously undocumented in the state.

One of the newcomers is Nomada banksi, a cleptoparasitic species. These bees do not collect their own pollen but sneak into the nests of other bees and lay eggs on the pollen they collected. In Clarion County, Master Gardener Kay John captured 14 of these bees in her backyard. Nomada often are confused for wasps because they don't resemble the stereotypical fuzzy bee, noted Nash Turley, a postdoctoral scholar in the López-Uribe Lab who created many training materials for the program.

Turley recently wrote a paper that compares the results from the lab's collections-based program with crowd-sourced observational data on iNaturalist, an app that allows users to record observations of plants and animals in nature using photographs.

"We documented nearly three times the amount of bee diversity than did iNaturalist in the same period of time," Turley said. "In the near future, we will use our collections data, as well as other data, to update state and county checklists and perform conservation rankings of bee species in Pennsylvania. We hope these will provide a baseline for future conservation efforts and raise awareness about bee biodiversity in the state."

Master Gardeners are vital to the project's outreach efforts. Many give presentations on topics such as bee habitats, overwintering and flower preferences. Some create fact sheets about different bee species.

Master Gardener Consuelo Almodovar shares information about a bee monitoring project during Bug Fest, hosted by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Photo: Penn State Master Gardener Program

A box of specimens was collected and prepared by Peg Friese. Photo: Penn State Master Gardener Program

Others write about aspects of the project itself, such as the unique method of collecting bees in soapy water. Once collected, the bees' hairs become matted, so Master Gardeners perform a process similar to a salon treatment. They wash the bees in mason jars with Dawn dish detergent and water, then use blow-dryers to restore their fluffiness, which is crucial for identification.

"The knowledge the Master Gardeners have gained through this training and research have greatly increased their ability to speak to community groups, schools and others through educational outreach," Sesler said. "Data on bee populations, their health and the factors affecting them can serve as compelling evidence of the importance of bees. It can raise awareness about the critical role bees play in our ecosystems and food supply."

Sesler and López-Uribe hope they can expand this project in Pennsylvania while extending its reach into other states where Master Gardeners can participate in comparable research.

"We've had a few years to utilize the protocols and make improvements so that other groups could start a wild bee monitoring project similar to the one we have here," Sesler said.

The program was born from a Science-to-Practice grant provided by the College of Agricultural Sciences Office for Research and Graduate Education and Penn State Extension. The grant program awards up to $10,000 a year to integrated research and extension teams to address pressing, complex challenges. Grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture also support the project.

Janton said the greatest thrill of the project is contributing to the natural history collection of bees.

"It's mind-blowing for me that the 500-600 bees I collect in a season can provide so much information about what's happening in the bee world," she explained. "A lot of things are based on money and what bees can do for agriculture, but the reward for us is what we're doing for ecology and the food web. We can say that we are sustaining wildlife in our yards — not just bees, but all the other pollinators as well."

How to Help Bees

- Embrace a messy yard. Spare some mulch and leave small areas of dirt between plants, as many bees dig tunnels or live in hollow stems.

- Grow bee-friendly plants. If possible, reduce the size of your lawn by planting more bee-friendly gardens or wildflower meadows. Consider color; bees are most attracted to white, yellow, blue or violet flowers.

- Reduce or eliminate the use of insecticides and herbicides. These chemicals in your garden can harm bees and other pollinators.

- Bees need water. Create a shallow water source in your garden or yard.

- Learn about the importance of bees. Share this knowledge with your friends and family. The more people know about the value of bees, the better chance there is for widespread conservation efforts.

- Support conservation efforts. Protecting natural habitats and open spaces where bees forage and nest helps to keep bees buzzing.

By Alexandra McLaughlin

Features

Predictably Unpredictable

Building resilient crops for a changing world

A Passion for Plants

Cultivating the future of plant science

A Force of Nature

Ag Sciences leads the new Center for Plant Excellence

Shaping the Future of Agriculture

New Dean's Leadership Council to help guide future in the College of Ag Sciences