Posted: January 9, 2025

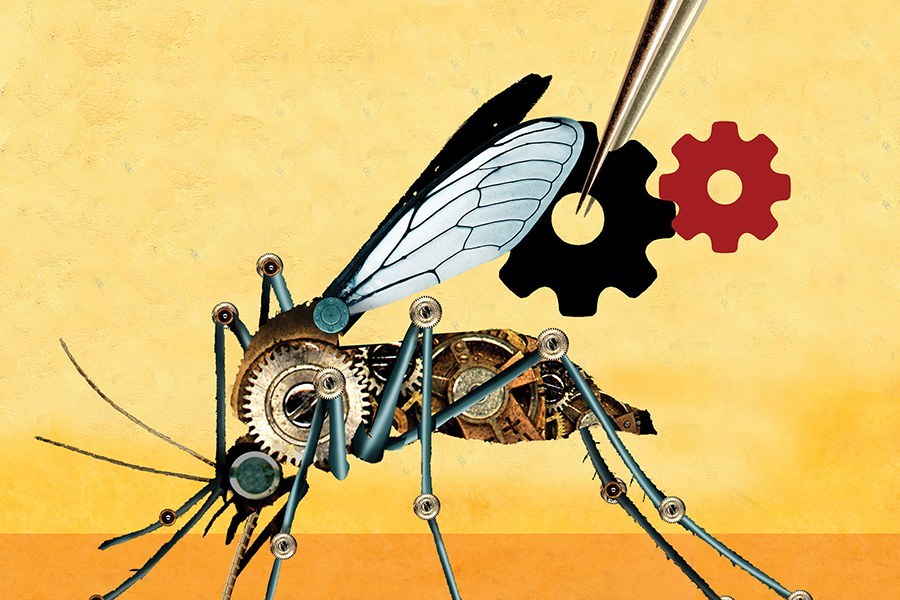

Research Targets Vector-Borne Diseases to Save Lives

Illustration: Michael Morgenstern

The deadliest animals on the planet are roughly the size of a black bean. Every year, they kill a population about the size of Dallas. Mosquitoes — specifically female mosquitoes, as they are the ones that bite — kill more people than any other creature on Earth by spreading pathogens that cause diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, West Nile, yellow fever, Zika, chikungunya and lymphatic filariasis.

A mosquito is a vector, a living organism that can transmit infectious pathogens to humans, and is among the many threats that researchers in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences are tackling by developing new tools, technologies and approaches to combat vector-borne disease.

"Mosquitoes are the most dangerous animal in the world," said Seth Bordenstein, professor of biology and entomology, Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck endowed chair in microbiome sciences, and director of the One Health Microbiome Center at Penn State. "They kill about a million people a year and cause about 400 million cases of vector-borne disease annually. With a real spirit of urgency and determination, we are developing solutions because millions of lives are at stake. Penn State is at the forefront of this imperative to make a difference in mosquito-borne diseases."

Bordenstein said that mitigating the spread of vector-borne disease is vital for safeguarding public health in a warming climate with increasing urbanization and crucially important for protecting economies and social stability in the regions where diseases spread.

"We're building capacities and investments to deliberately change mosquitoes from ones that transmit disease to ones that can't, which could fundamentally change humanity's disease burden and livelihoods in which these vectors thrive," he said.

The college recently launched an initiative focused on fostering collaborations across disciplines to combat vector-borne disease. This important initiative will leverage scientific contributions from researchers in a wide range of fields, such as entomologists who specialize in the biology of vectors, wildlife ecologists who analyze animal host reservoir populations, epidemiologists and behavioral scientists who study the broader behaviors affecting disease spread, public health experts who can develop prevention strategies, microbiome scientists who track disease agents and engineer beneficial microbial associates of mosquitoes, and data scientists who glean insights from patterns.

Adapting to adaptation

Vector-borne diseases are transmitted by animals or "vectors" such as mosquitoes, ticks and fleas, which spread pathogens through their bites. The diseases they transmit pose significant threats to human health, causing illnesses such as malaria, dengue fever and Zika virus; the environments in which they can survive, or even thrive, are rapidly changing due to a warming climate and expanding human development. This year, Latin America experienced its worst dengue fever outbreak on record, and in 2023, the U.S. experienced its first instances of locally acquired malaria in more than 20 years.

Erika Machtinger, associate professor of entomology in the college and leader of Penn State Extension's vector-borne disease team, explained that climate change is making the problem worse by creating favorable environments for vectors in previously lower-risk areas. She added that pathogens spread more readily as human populations become more mobile and move to newly developed areas.

"One of the main concerns for pathogen risk due to climate change is vector-borne disease," said Machtinger. "They're very complicated systems. Vectors are living organisms moving around, often feeding and living on other living organisms, and responding to the complexity of climate and environmental change.

Machtinger's work involves navigating the complex interactions among pathogens, vectors and their animal reservoir hosts — all in a rapidly changing environment. To her, human behavior is arguably the most important piece of that puzzle: Will people dress appropriately to avoid tick and mosquito bites? Will people remove tall grass and standing water from their yards to eliminate breeding habitats? Will people eventually accept the Lyme disease vaccines that are now in human trials?

"We have to take a more holistic approach," Machtinger said, explaining that her team has partnered with researchers in the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications, the Survey Research Center and the Department of Sociology. "I'm an entomologist, so I am totally out of my lane. This is not just about bugs — it's about people and understanding how they behave and finding effective ways of communicating with them."

Leading the nation

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention named Penn State as the lead institution for one of five new Vector-Borne Disease Regional Training and Evaluation Centers. With a projected $6.5 million in CDC funding over five years, the University will work to enhance national efforts to prevent and control vector-borne diseases

"Our approach is unique because we are very focused on extension and evaluation," said Machtinger, who serves as project lead. "The idea is to coordinate with organizations throughout the entire region and develop toolkits for people who may not be experts in vector-borne disease. We're serving as a mechanism for connectivity."

In 2019, Machtinger established the Penn State Extension vector-borne disease team, the first of its kind in the nation, to address the growing crisis in Pennsylvania. The team offers an abundance of resources to the public, including information about common ticks and mosquitoes in Pennsylvania, vector-borne diseases and vector management.

Lyme disease, caused by a bacterium transmitted to humans from infected black-legged ticks, is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States — and Pennsylvania has had the nation's highest incidence of the disease for 11 of the past 12 years of data, according to the CDC. It's why the Lyme disease vaccine currently is being trialed in Pennsylvania, Machtinger said.

"But it's not just Lyme disease we're worried about," she said. "There has been a notable increase in tick-borne diseases generally. We attribute at least some of this to ticks expanding their geographic range with changes in climate and landscape use."

Her team is working with researchers at the college's Deer Research Center to study how varieties of ticks interact with deer hosts as the climate changes. Early analysis has indicated that lone star ticks, which carry a pathogen that causes alpha-gal syndrome, a potentially life-threatening allergy, may outcompete black-legged ticks if they are feeding in the same locations.

Her team also evaluated the effectiveness of treating wild white-footed mice, the common hosts for black-legged ticks, by placing cardboard tubes containing acaricide-treated cotton in their habitats so the mice would use the material in their nests. The strategy effectively reduced populations of black-legged ticks.

"It was a promising finding that we could potentially take out the Lyme disease vector in some areas. But we could run into the issue of having another tick species, such as the lone star tick, which is very aggressive, take its place," Machtinger said.

Fighting disease with bacteria

One promising solution for mitigating the spread of vector-borne disease is a common bacteria that occurs naturally in roughly half of all insect species, including bees, beetles, butterflies, moths and fruit flies. The bacteria, called Wolbachia, poses no health risks to humans or animals. However, it blocks viruses such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika from growing in the bodies of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, reducing their ability to transmit viruses.

A recent study led by Bordenstein and other microbiome researchers at Penn State found that Wolbachia and the virus it carries also can cause sterility in male insects by hijacking their sperm, preventing them from fertilizing eggs of females that do not have the same combination of bacteria and virus.

—Adrienne Berard

Features

Predictably Unpredictable

Building resilient crops for a changing world

A Passion for Plants

Cultivating the future of plant science

A Force of Nature

Ag Sciences leads the new Center for Plant Excellence

Shaping the Future of Agriculture

New Dean's Leadership Council to help guide future in the College of Ag Sciences